GoodBuffer

In networked environments, communication consists of two computers exchanging raw bytes, where both sides must not only be able to transmit and receive data, but also interpret the resulting byte stream according to a shared language and protocol. This is embodied in two tightly coupled programs that implement the same data model and communication semantics. Transformation from in-memory data structures to byte streams is referred to as encoding (serialization), while the inverse process is known as decoding (deserialization). Without a reliable and unambiguous way to encode and decode data, interoperability and correctness cannot be retained and thus communication is not possible.

To address this, the software ecosystem has emerged up to this date to establish a set of standards, which, for the sake of this article, I will separate into self-describing and schema-driven formats. For instance, self-describing formats like JSON, XML and YAML prioritize human readability, flexibility and portability, and are supported by stable implementations across most programming languages. On the other end are schema-driven formats such as Protocol Buffers, FlatBuffers, and Cap'n Proto, which rely on explicit, developer-provided schemas to generate encoding and decoding code ahead of time, enabling not only very efficient binary representations and improved runtime performance, but also statically typed data structure guarantees when decoding.

From early on in my involvement with software engineering, it has seemed intuitive that computers do not need to communicate through self-describing formats. Since the programs on both ends are coupled, developers have the flexibility to define exactly how messages are laid out for both sending and receiving, which allows us to omit the overhead that self-describing formats carry. However, we have to acknowledge the challenges of maintaining proper compatibility; most actively worked on programs get new requirements over time, which lead to developers having to tweak the data layout of transmitted data, like adding and removing fields or changing a field type entirely. Since one of the key benefits of schema-driven formats is the compactness of the binary data, these usually omit field names and type information, and expect both ends to agree on an identical data layout.

The beauty of self-describing formats is the unambiguity of field names and types in all messages; thus, the client can check for the absence of fields and validate types after decoding the received payload, so it does not accidentally misinterpret data on an outdated version. At the other extreme, sending the most raw and compact binary representation of our data would neither include type information nor any guarantees on field types as well as their order, which will inevitably break compatibility from the slightest change in data layout.

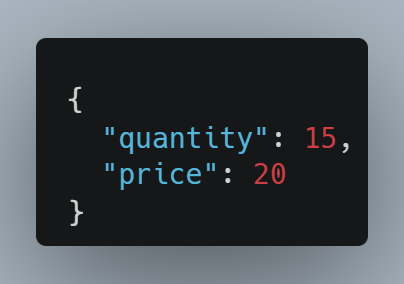

- The presence of field "quantity" and "price"

- Both "quantity" and "price" having the JSON number type

- Value 15 and 20, respectively

Attempting to query and process these fields with their values will result in an easy-to-detect runtime error if a malformed JSON object is received that does not meet the aforementioned requirements. This behavior is guaranteed by the included data layout, as well as by the implicit and unambiguous typing of values defined by the JSON standard.

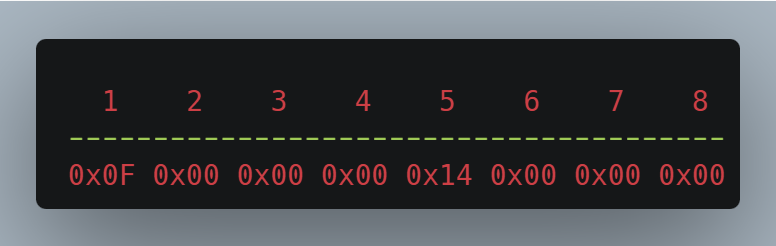

On the other hand, this highly compact binary representation shown in Fig. 2 of the same object has two 32-bit (4 bytes) unsigned integers laid out next to each other for "quantity" and "price" respectively, taking a total of 8 bytes. The JSON message above - assuming a minified version and UTF-8 encoding - requires 26 bytes to convey the same information that the receiver cares about. Here however, the values themselves are the only information included; this requires both the server and client to share an identical data layout.

What happens if we later add another field like "currency"? If we remove one of the both fields, how would an outdated client know which field is left? If 32-bit integers are no longer sufficient to encompass the potentially biggest possible quantity or price, requiring a transition to 64-bit integers? Or if the field order of "quantity" and "price" is swapped, causing the client to misinterpret the message entirely. Self-describing formats such as JSON evidently provide the ability to determine, whether the received data meets the program's expectations in a fail-safe manner.

Therefore, schema-driven formats usually include minimal meta information in the encoded byte stream to guarantee compatibility across schema evolutions to a certain extent. For instance, Protocol Buffer includes a field tag in the binary representation - unsigned integers preceding each value - which allow clients to handle absence of known fields and safely ignore unknown ones. FlatBuffers does not rely on field tags and instead encodes a "vtable" at the start of each object, which includes the address offsets of each field to locate their values; an offset of value 0 indicates the absence of a field. Additionally, it does not rely on numeric field tags like Protocol Buffers do (but allows it optionally); instead, field order in the schema determines the layout, so new fields must be added to the end of a table. Cap'n Proto, by contrast, neither encodes field tags nor "vtables": each field has a fixed offset within the message, and the transmitted struct's data layout includes the size of data and pointer sections, which the decoder uses to skip unknown fields.

Backward-compatibility can break if field tags are reused, types are changed, or fields are removed entirely. All of the aforementioned schema-driven formats rely on the developer strictly following evolution rules, like the use of deprecation annotations to mark removed fields, so newer decoders can skip those offsets to maintain compatibility. FlatBuffers goes one step further by distinguishing structs and tables: structs are fixed-size, inline, and can neither be evolved nor deprecated, whereas tables are flexible and maintain compatibility like in traditional schema-driven formats.

- Generated client code depends on libraries written specifically for the target language, many of which are community-maintained and thus not reliable and in danger of becoming outdated and, in worst case, incompatible with mainline releases. While I do have an understanding that maintaining community-based library bindings can be a thankless job; in practice, that has become a shortcoming when using Cap'n Proto with JavaScript and not having a single library (see here), that works properly with the latest stable Cap'n Proto version due to the library's inactive development.

- While most scalars and simple vectors are covered in the built-in types, only proto3 includes a (limited) map/key-value container equivalent and none of the schema-driven formats includes explicit nullability/optionality, which can be distinguished from actual field absence; that behavior has to get reimplemented by the developer. These (Link 1, Link 2) articles go into great detail about these issues, specifically the questionable "everything is optional" approach of Protocol Buffers.

- Protocol Buffers is the most well known (and mature) schema-driven format by Google, is very well covered in language support and, additionally, tightly integrated in the gRPC ecosystem. When it comes to encoding and decoding speed however, it lacks random access to fields unlike Cap'n Proto and FlatBuffers, and is much slower to encode and decode due to its tag-based nature, and variable-width integers (varint) in order to save space for small integers; consequently encoding/decoding those is much slower and requires arithmetical operations to do so. Despite of this, Protocol Buffers remain to be the most widely used format; encoding/decoding speed does not seem to be a bottleneck for big companies.

- Cap'n Proto's biggest focus is instant encoding/decoding, which is being accomplished by having their platform-independent data interchange format match the in-memory representation; this is very useful for companies that have to process enormous amounts of data over the wire, but without additional compression, it takes much more space on the wire due to its encoding specification, which heavily utilizes cacheline-friendly locality for the struct/list pointers as well as padding for natural field alignment.

Before getting into the "Why" of this chapter, this has been one of my biggest question marks before starting this journey:

Is it truly necessary to maintain perfect backward-compatibility?

The reality is that in many real-world applications, backward-compatibility does not have to be maintained, and could even be undesirable. To take an example, most multiplayer video games run servers, that require all connected players to run their game client on the latest version, or simply put: clients have to run on the exact same version as the server, or connection will not succeed. Their developers can and will gladly break any kind of backward-compatibility in the data layout and neither want nor have to think about adding field tags to each field, or being told, that they are not allowed to change types or field order. Fast performance and minimal bandwidth usage are also desired, since game packets have to be encoded and decoded fast and transmitted concurrently many times per second to thousands or even millions of players.

On the contrary, many live service applications with potentially long-lived clients want to maintain compatibility where clients that run one or more versions behind need to stay in the most functional state possible. Thus, a good schema-driven format should be capable of satisfying both approaches based on application requirements, as demonstrated by FlatBuffers with its struct and table differentiation.

- Developer-friendly schema language, which does not enforce unintuitive rules and supports scalars, explicit nullability and vectors/maps without considerable restrictions (e.g. Protocol Buffers does not support map values to be of type map), whilst providing much flexibility in evolution. I have innovated a lockfile system in this context in order to accomplish an intuitive developer experience with schema evolution, which I will detail later in this article.

- Minimal, independent generated code: GoodBuffer can be easily extended to support all programming languages that have built-in primitives to read, write, and interpret bytes, without relying on external libraries and reducing project dependencies. It was very important to me that language bindings should be easily maintainable and provide intuitive interfaces to the users by keeping the data layout specification simple as well as the code generation.

- Highly compact binary representation over zero-copy reads like Cap'n Proto, memory padding like FlatBuffers and tag-based binary representation like Protocol Buffer - instead, GoodBuffer aggressively inlines data with minimal information attached for variable-length fields, and natural alignment of values (which FlatBuffers achieves through memory padding) is not a priority.

- Modular and composable build system, which powers the CLI application, the LSP (Language Server Protocol) Server to power modern IDEs, and is designed to support strong debugging tools in the future to inspect GoodBuffer binary data in human-readable format.

Conceptualizing GoodBuffer was, by far, the most challenging and time-consuming task of this project; at the start of 2025 when development started, the landscape of self-describing and schema-driven formats was already well established, so finding room for further gains to innovate the kind of technology that I would like to use in my daily life as a software engineer required me to deep dive into the specifications and implementations of the aforementioned schema-driven formats. The following is a brief presentation of my plans before diving into implementation.

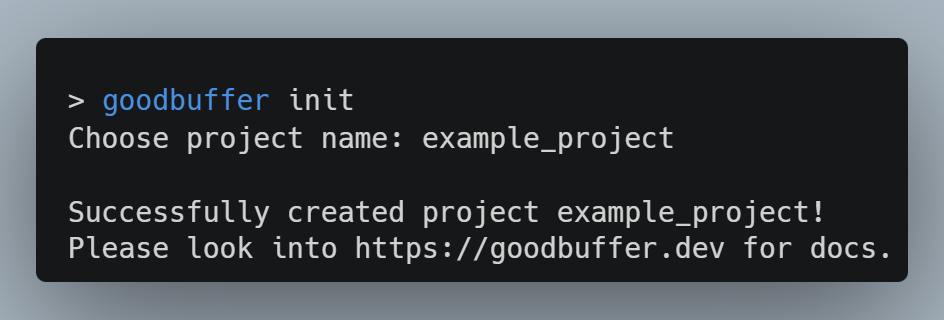

CLI:Similar to other schema-driven formats, I decided to make GoodBuffer a standalone CLI application that is responsible for compiling language bindings from .goodbuffer-schema files to encode and decode the data structures according to my binary specification. Additionally - one of the very few opinionated rules - I enforce a project structure where the project folder consists of a "project.json" next to all the ".goodbuffer" files inside the root folder and subfolders. Using the command "goodbuffer build [relative_path_to_folder]" will build the project with all its export targets.

Initializing a new project is as easy as demonstrated in Fig. 3; this creates a subfolder in the current working directory with a basic "project.json" and first goodbuffer schema.

The contents in Fig. 4 show an examplary "project.json" of a GoodBuffer project. The bare minimum requirement for a valid project is the existence of at least one target in the "targets" array, where each target represents an export configuration with specificied output path of the generated code as well as the programming language. The optional "features" array in each target allows the use of more modern standard libraries for (de-)serialization, but by default, the empty feature-set aims to cover wide support for the given programming language.

To illustrate, providing "span" to the feature-set of a C# output target allows the GoodBuffer compiler to use the Span-API (introduced in C# 7.2) for improved serialization performance. For JavaScript, we could also provide a Node.JS feature that makes use of the Node's Buffer-API (specifically Buffer.allocUnsafe and Buffer.concat) for faster performance, whereas equivalent implementations for browsers lack behind.

In the future, I will add options to the "project.json" for the formatter, which is a planned feature that formats the schema files on each compilation to a standardized format that is configurable (e.g. tab spaces) through the project file; similar to prettier. This would enforce consistency, thereby enhancing collaboration and ensuring clarity in larger projects.

Schema Language:

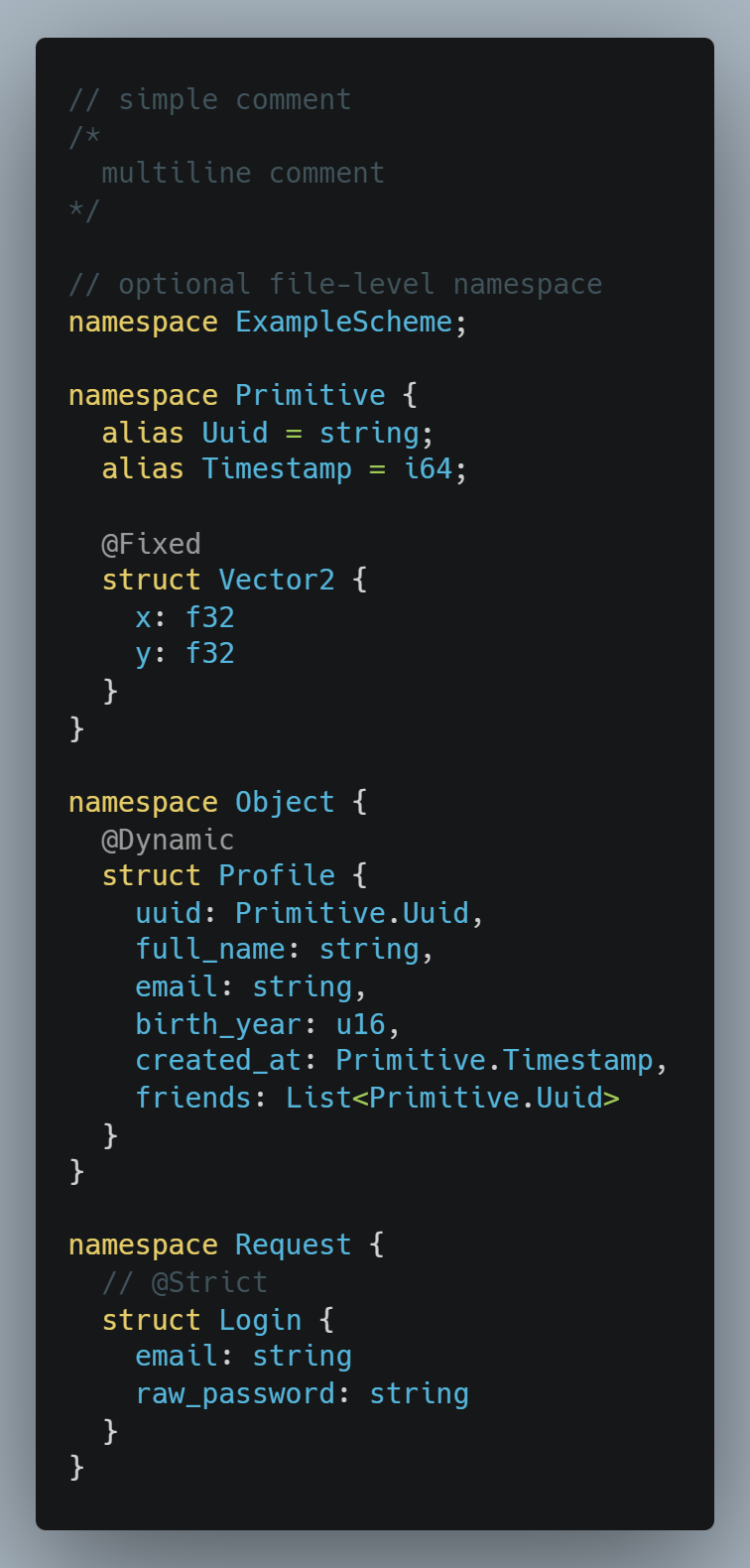

Here in Fig. 5, you can see a minimal example of how a GoodBuffer schema can look like. All data structures are defined with "struct", scopes and semantic nesting are achievable through namespaces, and additionally, you can define aliases for types. Writing a one-line namespace definition at the top of the schema file encompasses the entire schema's content to be inside that namespace. Last but not least, structs can optionally be annotated with @Fixed, @Dynamic or @Strict, with @Strict being the default mode of each structure, which I am going to elaborate on later.

- Semicolon after file-level namespace and alias definitions are optional

- Commas after struct fields are optional

- Each pritimive data type has multiple variants, e.g. a signed integer can be described as "i32", "int32" and "int"; boolean can be described as "bool" and "boolean"; lists can be described as "List<type>" and "type[]", and so on.

- GoodBuffer's auto-formatter feature allows you to optionally enforce a specific style over all schema files of the project based on your preferences, like enforcing a comma after each struct field, the generic List notation over square brackets, or the short-hand "Rust"-like notation for primitive datatypes such as "i32".

In my opinion, this feature is a game-changer since it allows developers to feel at home when managing a high amount of data structures, while the auto-formatter ensures consistency so the preferences of various developers working on the same GoodBuffer project do not clash against each other.

- @Strict (the default) mode offers a reasonable trade-off between fixed and dynamic structures, and allows for schema evolution the same way that current schema-driven formats do: Removing fields entirely is prohibited, and instead has to get deprecated by adding a @deprecated annotation above the field. Changing types of existing fields is also not allowed without fundamentally breaking backward-compatibility. Adding fields is allowed and order does not matter (does not have to be added at the end of the structure).

- @Fixed is the mode that includes zero meta-information inside the binary representation and achieves the most efficient size and performance by not providing any mechanics to establish compatibility; this is ideal for fixed primitive data structures like "Primitive.Vector2" in Fig. 5 and the application requirement of not having to guarantee compatibility.

- @Dynamic is a mode that might seem counterintuitive to the reader at first glance since this one serializes structures in a self-described binary format (inspired by MessagePack). It is useful for highly flexible and often-changing structures that are not utilized in environments with high performance requirements. There are no restrictions to the schema evolution at all, however it follows an optional-first principle where each field is nullable due to the dynamic nature. Furthermore, the developer receives both the benefits of typed access and the capability to dynamically query fields in a JSON-like style; the decoder tries to fit the received data to its known data layout, and also upcasts types if compatible, for example a received int32 to the known int64 field. In case of field absence or incompatible typing, affected fields will be null and have to get dynamically queried.

It is also worth mentioning that in GoodBuffer, fields can be renamed and their order does not matter, regardless of mode. On each compilation, the identity of all structs (a bundle of all field names and their types) is saved inside a lockfile. If the struct already existed in a prior compilation, the old field order is applied, and renaming a field can be detected by a temporary @RenameTo(NewName) annotation that developers add to fields that they want to rename; this will trigger the lockfile to add a remapping from the new name to the original field, and GoodBuffer's auto-formatter removes the annotation and substitutes the field name post-compilation.

- Zod-inspired validators, which add additional safeguards during (de-)serialization like ensuring that a string's length is in between a provided range, string contents matching a certain regex (for example an email address), and so on. For this, I would provide simple constructs in the schema language that can then be transpiled properly to all possible target programming languages.

- Integrated support for diffs and patches: a common scenario in software

development is sending out updates to clients that have to apply those

to the in-memory state. Servers do not want to send the entire state on

each update since that would massively increase bandwidth and

deserialization time for clients; instead, it sends the difference

between the client's last known state and the new state, so that the

client only has to "redo" the changes. This is a related project of mine

that implements this behavior for JSON... ... and I personally think that this is also a feasible endeavour for GoodBuffer. A very simple way to accomplish this on the schema-side of GoodBuffer would be to provide an annotation like @WithPartial that can be attached to structs, to mark the generator to generate partial data support.UltraPatchJSONPatch library in TypeScript with focus on performanceCore LibraryTypeScript

- Custom datatypes provided by the developer inside a schema file that can include native code inside a "native { ... }" block for custom (de-)serialization, e.g. a custom "Date" type. Useful to bridge library/application types from the application to GoodBuffer.

For the binary specification, I followed the same approach as Protocol Buffers and prioritized compactness over random-access and zero-copy. As a result, the generated code remains minimal and independent of third-party libraries, and the bytestreams over the wire are smaller, without significantly compromising (de-)serialization performance.

- Fixed structs serialize to all fields inlined with no meta information included

- Dynamic structs include field names and type tags preceding the value, which can represent all scalar, collection, and user-types, in the bytestream; similar to MessagePack

- Strict structs are being handled differently: Each struct object starts with the total size of the struct object and a bitset that marks field presence/absence with 1's and 0's respectively. Each byte of that bitset ends with a continuation bit , that marks if the bitset goes on to the next byte, so the size of the entire bitset depends on the amount of struct fields and the last present field. If no fields are present, the bitset would be 0 and the encode function returns an empty bytestream that has the same semantic purpose. This bitset is important to distinguish the default/null value of a field from an actual absence. It also allows for older decoders to ignore newer fields that are unknown, and to ignore new, unknown fields by skipping to the end of the object with the total size that is included at the start.

Next up, all fixed-size primitive datatypes like numbers are encoded raw and little-endian; the only exception is boolean, where a struct with multiple boolean fields packs all booleans together with each boolean taking one bit, thus each byte can hold up to 8 booleans. Strings, lists and maps are preceded by their length, which, in my current design, take up 4 bytes in order to support large datasets. Maps are simply encoded as a list of keys and values; in the end, the language implementation bears responsibility to store the map as a hashed container in memory or not.

Tech-Stack:- Fast terminal interface for the CLI

- Native filesystem access to read project.json and the .goodbuffer schema files, as well as output generated code

- Has to be able to parse .goodbuffer schema files and project.json quickly

- Portable, lightweight executable

- RefCell is much slower than a direct access

- Using unsafe Rust code, which invalidates the whole purpose of using Rust in the first place

So in order to not fight with Rust's borrow checker, I went with Zig, which turned out to be a new and very fresh experience for me to write in a low-level programming language. Most notably, the comptime feature for executing code and manipulating types at compile-time, the built-in memory allocation implementations like the arena allocator, the defer-feature for organized resource cleanups, and the goto-switch feature came in very handy.

The two aspects that I want to highlight in this chapter are the schema parser and the overarching build pipeline. Initially in the Rust implementation, I first wrote the schema parser in TreeSitter, and later on in Pest because I did not like the significant overhead of TreeSitter. After the switch to Zig however, I decided to take the challenge of handwriting the parser, first due to lack of a good Pest-equivalent library in Zig, and secondly because I wanted more control over the parser, which allows for detailed error messages to the user writing the scheme. Below, I included a glimpse of the parser implementation for anyone who is interested:

With just a little over 400 lines of code, this already is a complete handwritten recursive-descent parser that constructs the abstract syntax tree (AST) directly from the source code and provides error context. Although there is still room for optimizing performance, a cleaner structure and proper test cases, it gets the job done and is extremely fast in my local testing: Goodbuffer is capable of running the entire build pipeline on a project consisting of a single 1 million line .goodbuffer scheme file (containing over 250,000 structs) in approximately 600ms on my machine (Ryzen 5 5600x), excluding file read and write times. Additionally, having a very fast compiler that can handle most ordinary GoodBuffer projects in sub-millisecond enables a highly responsive language server to significantly improve developer experience; for that, a fast parser implementation is indispensable.

Most language compilers include a tokenizer, whose sole responsibility is to read the raw textual input and produce a stream of tokens, before the parser consumes that stream to construct the AST. Those tokens include information such as its kind, which for instance can distinguish an identifier from a brace, and the token's content. In my case, I have to parse a schema with fairly simple and unambiguous lexical rules; thus, I skip the intermediary production of tokens and generate the AST directly. Although this might seem like a violation of clean code principles such as the lack of separation of concerns, this approach entails a performance improvement: memory is slower than the CPU, and we can skip the allocation of tokens as well as the iteration through them in the second pass, which also likely leads to cache misses.

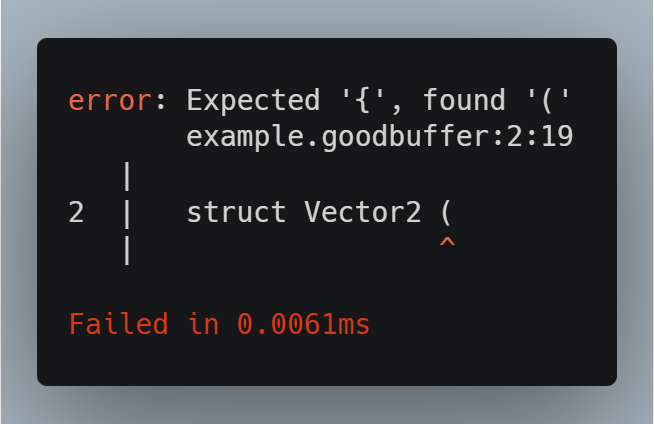

Connected to the parser is also the CLI functionality for pretty-printing errors inside the terminal. The error context provided by the parser just contains the error description in "message" and the failure-causing slice of the source code. In Zig, a slice is an internal data structure that contains both a pointer and length. Thus, with simple pointer arithmetic that you can see in lines 10 to 20, I am able to determine the source file of the error without including the source file reference inside the error context by doing simple range checks. Consequently, I can safely determine the entire line of code that surrounds the failure-causing slice (because most errors do not encompass the entire line), add red arrows below that line for the error-causing slice and finally pretty-print it in the CLI.

This is what it looks like in practice:

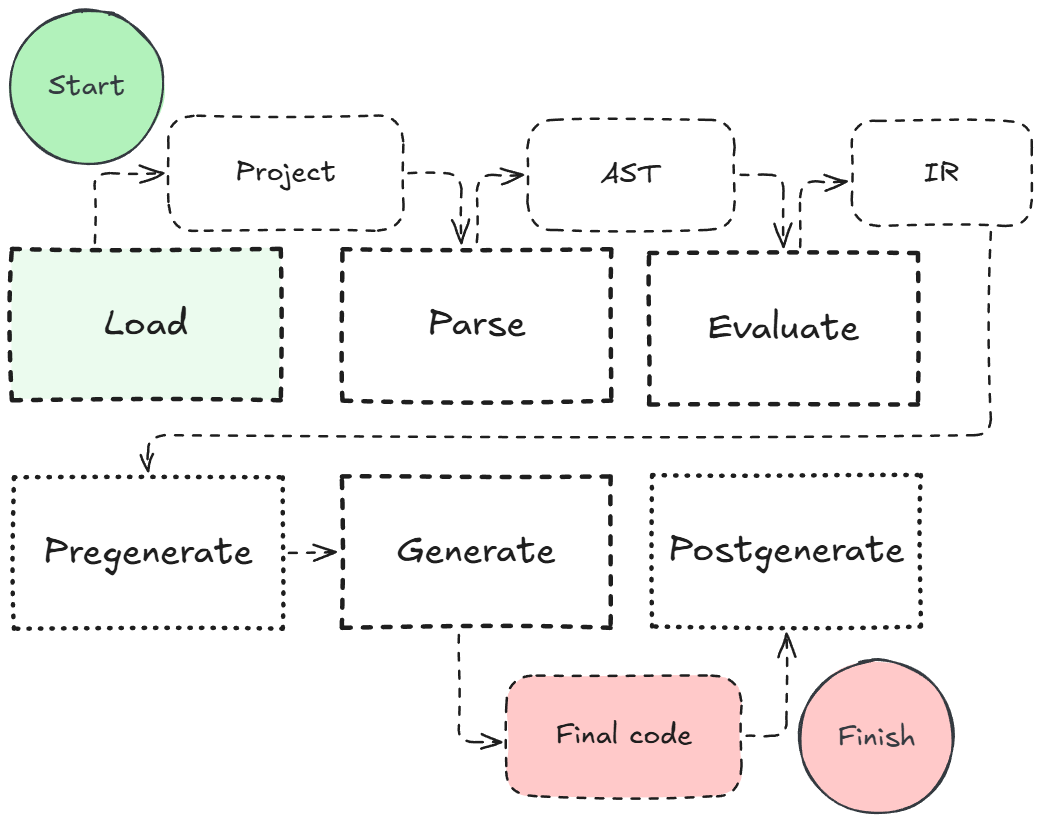

Now, with the parser ready to use, we still have to generate fully functional source code from the AST with both serialization and deserialization logic. The serializer and deserializer require full knowledge of the data layout, relationships between structs in different scopes, evaluated alias types, and more. Additionally, the compiler provides auto-formatting and lockfile handling, which is just as important. Here is a quick breakdown of how I designed this modular build pipeline and how I am utilizing it.

- Load: Loads the "project.json" configuration and all schema files into memory. Consequentally, the project configuration file is checked for validity and on success, both the valid configuration and the raw contents of all schema files are packed and returned inside a "ProjectContext" bundle structure.

- Parse: Parses all provided schema files into AST's.

- Evaluate: Evaluates scopes, types (which includes scope traversal), aliases and guarantees, such as unique identifiers inside a scope to avoid collisions and that no struct is infinitely recursing (in the simplest example, field of struct is struct itself). Returns an intermediate representation (IR) that represents a fully validated schema tree structure for each scope and struct, and proper type references.

- Pregenerate: Updates the lockfile with new mappings and names.

- Generate: Constructs the schema operations from the IR and generates the final source code.

- Postgenerate: Runs auto-formatter on schema files.

The advantage of separating the individual build steps is that that LSP Server can decide to just call the parser and evaluator to obtain the required information. Additionally, isolating the parser allows us to parallelize the parsing of each schema file: Contrary to the evaluator, the parser does not need context of the other schemas to parse an individual schema file, so I am utilizing a thread pool where each thread handles exactly one schema file at a time.

It is also worth noting that the whole build pipeline is fundamentally designed to be run with arena allocators. Due to the short-lived nature of the build task, it is both efficient and memory-safe to perform all heap allocations for the AST, IR and schema operations on an arena allocator. After the build is done, we simply just have to deinitialize the entire arena at once, which inherently makes memory leaks impossible and simplifies memory management because the responsibility of deallocating singular objects is gone.

Last but not least, the generator infers the required operations in both serialization and deserialization from the IR; those operations declare which bytes have to be read and written to, which is specifically important for dynamic objects like strings and lists that require preceding information such as length. That is the last abstraction layer that we pass to the language code generators; then, their only responsibility is to translate the provided operations with the language-equivalent functions, and thus can stay minimal in implementation.

Although I have mentioned in the beginning of the previous chapter (see here) that the implementation is currently missing very notable features of GoodBuffer's specification, the fundamental architecture inside the implementation is set in stone and adding the missing features is mostly just a matter of time and would not require much conceptualizing. I genuinely believe in the potential of this project and that it could solve real-world issues, enhance developer productivity and beat the established schema-driven formats in data compactness over the wire in the future. However, it is important to not neglect that in reality, Protocol Buffers and the other formats have their own advantages and unique features (like first-class RPC support) in which they exceed GoodBuffer's capabilities without a doubt, and particularly that they have been around for many years and well-tested in production. In fact, even the advantages of GoodBuffer do not necessarily matter, because those formats are "good enough" for most users in those aspects that it does not matter in the real world. Additionally, growing the project in the open-source realm with a community that can contribute and test changes into a state where GoodBuffer will be considered a mature player in the field is a years-long process that would require much dedication, time and patience.

- Going through the whole process of creating a detailed documentation of my own language with its syntax, binary specification, and the entire build pipeline was a new and pleasant experience for me.

- I have researched and understood the internals, trade-offs, and focus points of Protocol Buffers, FlatBuffers and Cap'n Proto. Cap'n Proto specifically made me do research on CPU caches and cache lines in order to understand their performance optimizations, which allows me as a programmer to make more performant data-oriented decisions as well as better comprehend and debug performance bottlenecks in all my projects.

- This was my first (and definitely not last) Zig project, and I have mastered the programming language with this project to a degree where I was able to help out many other programmers with their questions in the official Zig community hubs.

Thank you for reading this article, if you would like to discuss this project, please feel free to contact me at emin-b@gmx.de.